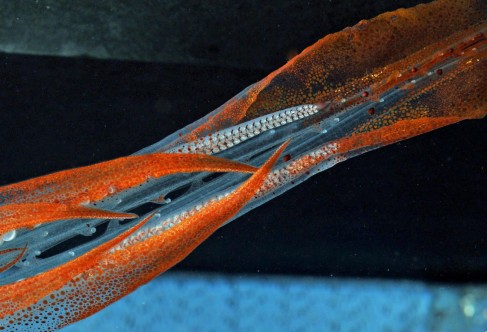

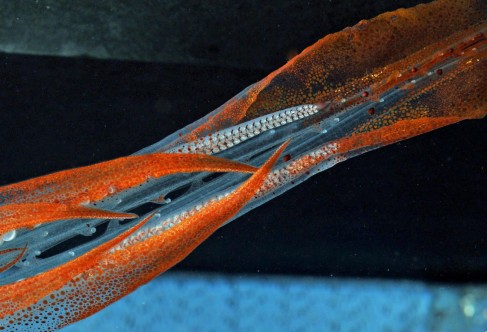

well, the vampire squid is a hard act to follow. although we did see some more very beautiful things, they’re all going to seem a little anticlimactic. so i’ll show you some nice photos of another squid anyway, Chiroteuthis calyx, which is more photogenic even if it doesn’t have the vampire’s notoriety, and i’ll tell you about something less sciency: life on the boat.

well, the vampire squid is a hard act to follow. although we did see some more very beautiful things, they’re all going to seem a little anticlimactic. so i’ll show you some nice photos of another squid anyway, Chiroteuthis calyx, which is more photogenic even if it doesn’t have the vampire’s notoriety, and i’ll tell you about something less sciency: life on the boat.

you can get a feel for the vessel itself, the western flyer (technical specs here) by taking a virtual tour. my overall impressions, compared to other ships i’ve been on (the rainbow warrior and academic ioffe), are that it feels very stable (although it has an interestingly unpredictable pattern of rolling, which we experienced during the first two days as the wind gusted up to 30 knots; still, nothing like the conditions that inspired me to write full tilt in 2004, reposted at the bottom of my ‘about’ page) and runs very quietly, although the noise from the hydraulic equipment for the ROV is significant. the common areas feel comfortable and spacious, while the cabins are extremely economical on space—the non-bunk floorspace in the double cabin i share is less than 2x2m, and that includes a sink and a desk. toilets/showers are shared between two cabins, so four people, but we’ve never had any timing crises that i’ve been aware of. maybe i’ve just been on the right side of the door.

the daily schedule goes something like this: ROV into the water around 0630, camera on and filming begins immediately. observers trickle into the control room to watch what’s going on any time over the next few hours (and drift in and out in the meantime); the live camera feed can also be viewed in the dry lab (where everyone’s computers are), the mess, the bridge, and on monitors in each cabin, so if you see something exciting come into frame, you can rush to the control room to share in the mass hysteria. breakfast is at 0730 and lunch at 1130; those operating the ROV (navigator, pilot, camera operator and video annotator) swap out about a half hour into each meal so everyone gets to eat. the food is consistently superb, unlike on some other voyages. the dive usually runs for 8–12 hours, depending on the goals for the day (sometimes there are two shorter dives), and that time is spent somewhere between 300 and 3000m on this trip, although doc ricketts can go to 6000m, with the entirety collected on film. during this time the ROV operators take shifts and the science crew are involved if data for their projects are being collected, or if they want to watch what’s going on (who doesn’t?!). dinner is at 1700 and the ROV is usually back on deck shortly thereafter. in the evening we’ve also been setting a short trawl down to 300–500m to collect pteropods, shrimp, jellies, and fish and squid that come to the upper layers as darkness descends. the net is hauled somewhere between 2000 and 2100 and then anyone with samples to process takes care of those. most people head to bed reasonably early after that, but i’ve been up late most nights, partly reporting here and partly because in my head it’s four hours earlier and it doesn’t make much sense to get readjusted for just a week. that does mean that the early mornings begin really early though; i confess to arriving at breakfast one morning to hear that i’d already missed five squid sightings by ‘sleeping in.’ a mistake i have not repeated.

so that may give you an idea of what life is like out here. it doesn’t convey—because words simply couldn’t—the overwhelming awe that this whole operation inspires, with its smooth running amid extremely advanced technology, innate expertise of those involved, and easy camaraderie among scientists and crew alike. it is an incredible privilege to be here, and photos like these, that can almost convey the magic of seeing these animals alive, will serve as a reminder for me (long after we’ve returned to the shore) of this wonderous week.

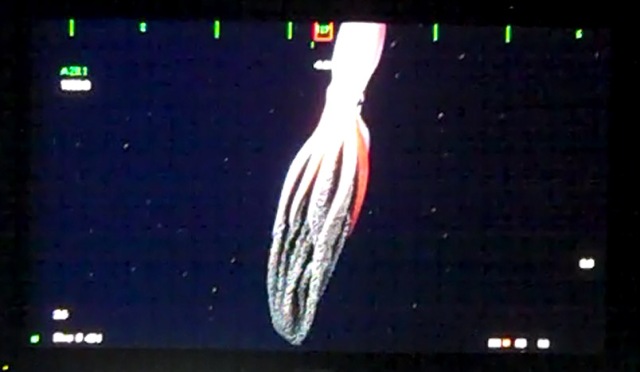

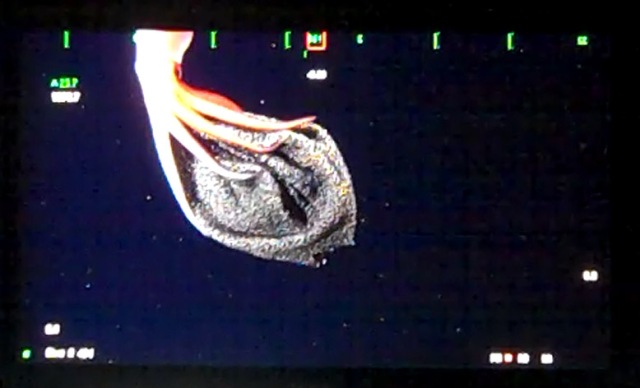

today’s theme is gelatinous octopuses. i never expected us to see any of these guys, let alone enough to make a ‘theme’, but over the past few days we’ve seen three: the Cirrothauma above, and two of the bolitaenids pictured below. i’ll tell you a little about them, as they are pretty remarkable. Cirrothauma murrayi (above) is a blind, finned octopus that seems to live in deep seas around the world; this one was 2.6 km below the surface when we saw him. (i say ‘him’ because he appeared to have a hectocotylus [modified reproductive arm found only in males]). mbari encountered another, much smaller specimen on a cruise this past july so it will be very interesting to see whether they are different growth stages of the same species.

today’s theme is gelatinous octopuses. i never expected us to see any of these guys, let alone enough to make a ‘theme’, but over the past few days we’ve seen three: the Cirrothauma above, and two of the bolitaenids pictured below. i’ll tell you a little about them, as they are pretty remarkable. Cirrothauma murrayi (above) is a blind, finned octopus that seems to live in deep seas around the world; this one was 2.6 km below the surface when we saw him. (i say ‘him’ because he appeared to have a hectocotylus [modified reproductive arm found only in males]). mbari encountered another, much smaller specimen on a cruise this past july so it will be very interesting to see whether they are different growth stages of the same species.